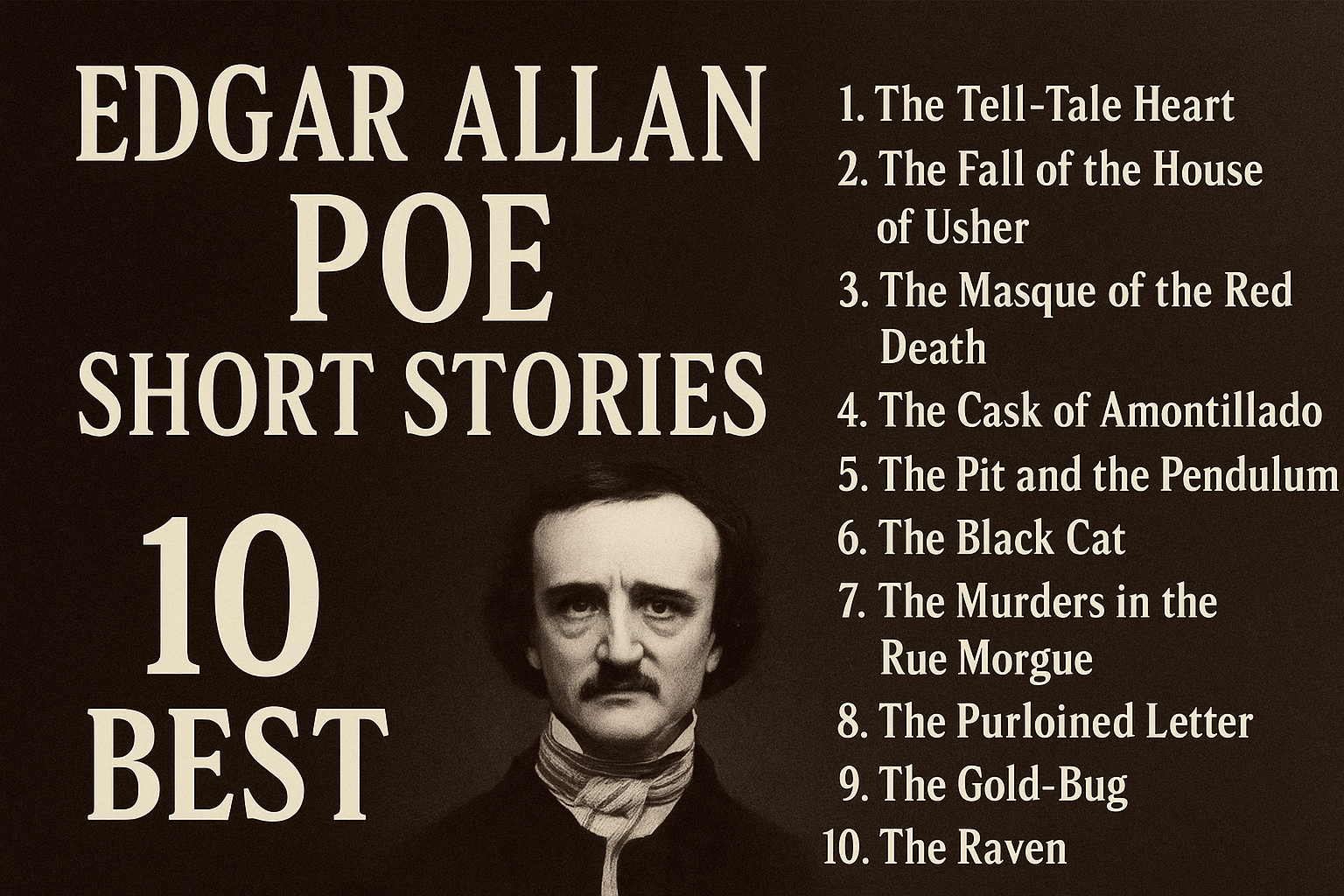

Edgar Allan Poe, the master of Gothic literature, is celebrated for his chilling short stories that blend mystery, horror, and psychological depth. His tales of madness, guilt, revenge, and the supernatural have influenced generations of writers and continue to captivate readers today. In this article, we’ll explore 10 of Poe’s most famous short stories, complete with detailed summaries, key themes, and why they remain timeless classics.

The Tell-Tale Heart (1843)

- Summary: A nameless narrator insists he is sane while recounting the murder of an old man whose “vulture eye” haunts him. After hiding the body beneath the floorboards, the narrator begins to hear the relentless sound of a beating heart, growing louder until he confesses his crime.

- Themes: Guilt, madness, paranoia, the fragility of the human mind.

- Why It’s Famous: Considered one of the greatest psychological thrillers ever written, it explores the torment of guilt and unreliable narration.

There was once a man who insisted he was not mad. He swore to anyone who would listen that his mind was clear, his senses sharper than most, and his actions guided not by madness but by careful planning. Yet, he could not hide the wild gleam in his eyes nor the way his voice quivered as he told his tale.

He lived in a small, dimly lit house with an old man. The old man had never wronged him never insulted or cheated him. Indeed, the narrator admitted that he even loved the old man, for the man was gentle in manner and had wealth that the narrator did not desire. No, the reason for his torment lay in one thing alone: the old man’s eye.

It was a pale blue eye, covered by a thin, filmy veil. Whenever it turned upon the narrator, his blood ran cold, and a chill gripped him as if Death itself had brushed against his soul. He came to believe that the eye was evil, a vulture’s eye, watching him, judging him, haunting him. Day after day, he felt its presence burning into his thoughts until he could no longer endure it.

And so, he formed a plan.

For seven nights, at the stroke of midnight, he crept into the old man’s chamber. Each night, he pushed the door open ever so gently, inch by inch, until a single narrow slit allowed him to extend his head inside. He held a dark lantern, its light hidden behind a shutter, so that not even a beam could betray him. Slowly, patiently, he would slide into the room, listening to the old man’s steady breathing.

But each night, though he longed to see the eye open, it remained closed. And with the eye closed, he told himself, there was no reason to act. After all, it was not the old man himself he hated only the dreadful eye. Thus, he watched, night after night, with the patience of a hunter, waiting for his chance.

On the eighth night, however, fortune revealed itself. As he opened the door, his thumb slipped upon the lantern’s clasp, making a faint noise. At once, the old man stirred in his bed. He sat upright in the darkness, his heart pounding, whispering into the empty air:

“Who’s there?”

The narrator froze, holding his breath, standing utterly still in the doorway. For a full hour, he did not move a muscle. The house was silent, the darkness pressing heavy against the walls. Yet he knew the old man was awake, straining his ears, his terror growing with each moment of silence.

Finally, the narrator opened the lantern just enough to let a single thin ray escape. It fell directly upon the vulture eye.

It was open wide, staring, pale, and terrible. At that sight, rage surged through the narrator like fire through dry leaves. His heart thundered in his chest, but it was not only his own heartbeat he heard. From the bed came a muffled sound, soft at first, then louder: the rapid, fearful beating of the old man’s heart.

Thump. Thump. Thump.

The sound filled the chamber, echoing in the narrator’s ears, louder and louder, until it seemed impossible that the neighbors could not hear it through the walls. The old man’s terror was feeding the sound, and the narrator feared the noise would betray them both.

In an instant of madness or what he still swore was reason he rushed forward, dragged the old man to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed down upon him. The old man struggled only briefly, then lay still.

The heart no longer beat. The vulture eye would trouble him no more.

When the deed was done, the narrator felt an exhilarating calm. He worked methodically, proudly, to conceal his crime. He dismembered the body with precision, cutting it into pieces that he hid beneath the floorboards of the chamber. He cleaned the room carefully, leaving not a single stain, not a single trace. When it was finished, he smiled. No human eye not even the vulture’s could detect what lay hidden beneath his feet.

It was four o’clock in the morning when there came a knock at the door. Three men entered officers of the law. A neighbor had reported hearing a shriek in the night, and the police had come to investigate.

The narrator welcomed them with confidence. His manner was cheerful; his words, friendly. He explained that the shriek had been his own in a dream, and that the old man was away in the country. He even brought the officers into the very chamber where the body lay beneath the floor. He placed chairs upon the planks, and in the height of his audacity, he sat directly above the hidden corpse.

The officers were satisfied. They spoke with him calmly, and he answered with ease. Yet soon, he began to hear a sound.

At first it was faint, distant, almost like the ticking of a watch wrapped in cotton. But it grew louder.

Thump. Thump. Thump.

The narrator’s smile faltered. He shifted in his chair, speaking more rapidly to cover the noise. But still the sound grew—steadier, heavier, louder, until it roared in his ears like a drum of war.

Thump. Thump. Thump.

He gasped for breath, his words stumbling, sweat pouring from his brow. Still, the officers smiled politely, speaking quietly among themselves, as if they heard nothing. This tormented him further. Did they not hear it? Or were they mocking him, pretending not to notice, while they laughed at his agony?

The sound was unbearable now, a furious pounding that shook his very soul. He clutched his head, his voice breaking into cries.

“Villains!” he shrieked. “Dissemble no more. I admit the deed, Tear up the planks. Here, here it is the beating of his hideous heart.”

And with that final cry, the secret was out. His own madness though he denied it until the end had betrayed him more surely than any evidence ever could.

Moral & Themes:

- Guilt cannot be buried. No matter how carefully one hides wrongdoing, the conscience will reveal it.

- Madness vs. reason: The narrator insists he is sane, yet his obsession and paranoia prove otherwise.

- The human mind is its own worst enemy.

1.The Tell-Tale Heart (1843)

Summary & Background

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart is one of his most famous short stories, first published in 1843. It is a masterpiece of Gothic fiction, exploring themes of guilt, madness, and the unreliable narrator. The story is short, but its psychological intensity has made it timeless. Many critics believe it represents Poe’s ability to blur the line between sanity and insanity, turning a simple crime into a chilling exploration of the human mind.

Plot (Full Detailed Retelling)

The story is told in the first person, through the voice of a narrator who insists on his sanity. From the very beginning, he addresses the reader directly, almost begging them to see that he is not “mad.” This insistence on sanity only makes his mental instability more obvious.

The narrator lives with an old man whom he claims to love and respect. However, he has become obsessed with one disturbing detail: the old man’s “vulture eye” a pale, filmy, blue eye that he finds intolerable. The eye, not the man himself, becomes the object of his hatred. In his twisted logic, he decides the only way to rid himself of the eye is to kill the old man.

For seven nights in a row, he sneaks into the old man’s room at midnight. He opens the door slowly and carefully, taking nearly an hour just to slide his head inside. He waits for the eye to open so that he can justify the murder, but each night the old man sleeps with his eye shut. The narrator says, “It was not the old man who vexed me, but his Evil Eye.” Because of this, he cannot bring himself to kill when the eye is closed.

On the eighth night, everything changes. As the narrator stealthily enters, his thumb slips on the lantern, and the old man wakes up in fear. In the darkness, the narrator stands silently, hearing the man’s terrified breathing. Then, he hears it: the beating of the old man’s heart. The sound grows louder and louder in his mind, filling him with uncontrollable rage. Believing the neighbors might hear it too, he attacks. He smothers the old man beneath his bed, ending both the heartbeat and the dreaded gaze of the vulture eye.

But Poe doesn’t stop there. The narrator carefully hides the body. He dismembers it, cutting it into pieces, and conceals them beneath the floorboards of the house. He does this with meticulous precision and feels triumphant at his own cleverness. No blood is left behind, no sign of a crime he is certain he has committed the perfect murder.

Soon after, there is a knock at the door. The police arrive, having been alerted by a neighbor who heard a shriek. Calm and confident, the narrator welcomes them inside. He tells them the old man is away, and he shows them the house proudly. He even brings chairs into the old man’s room, placing them directly above the hidden body.

At first, the conversation is pleasant. The narrator is at ease, smiling and joking. But then, he begins to hear something faint: a low, dull, rhythmic sound. It is the beating of a heart. At first, he believes it to be his own. But the sound grows louder. Louder. Louder. He becomes convinced it is the old man’s heart still beating beneath the floorboards. The noise consumes his thoughts, echoing in his ears until he cannot bear it any longer.

Driven into madness by guilt and the phantom sound, he breaks. He shrieks at the officers: “Villains! Dissemble no more! I admit the deed! tear up the planks! Here, here! It is the beating of his hideous heart!”

Thus, the narrator’s attempt at the “perfect crime” is undone by his own conscience, or perhaps by his descent into complete insanity.

Themes & Analysis

- Madness and Sanity The narrator constantly insists he is sane, but his actions and obsession prove otherwise. Poe uses irony here: the more he argues, the less convincing he becomes.

- Guilt and Conscience The phantom heartbeat symbolizes the weight of guilt. It grows louder as the narrator’s conscience eats away at him, showing that no crime can be perfectly hidden.

- The Unreliable Narrator We see everything through the eyes of a murderer who cannot distinguish reality from imagination. This makes readers question: did he really hear the heartbeat, or was it only in his mind?

- Obsession The narrator doesn’t hate the old man, but the fixation on the “vulture eye” drives him to murder. Poe shows how irrational obsession can spiral into destruction.

Why It’s Famous

- One of the best examples of Gothic horror in American literature.

- Frequently studied for its psychological depth and use of unreliable narration.

- Its brevity (a short, intense read) makes it accessible, yet its meaning is endlessly debatable.

- It has been adapted into plays, films, radio dramas, and even comic books.

Moral / Message

Even the most carefully hidden sins cannot escape the voice of conscience. Guilt will always find a way to reveal itself.

2.The Black Cat (1843)

Summary & Background

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Black Cat, published in 1843, is a chilling tale of violence, guilt, and psychological torment. Much like The Tell-Tale Heart, it is told by an unreliable narrator who insists on his sanity, even as he recounts increasingly horrific crimes. This story delves into themes of alcoholism, cruelty, domestic violence, and the supernatural, making it one of Poe’s darkest works. It combines real human weakness with eerie, almost paranormal consequences, blurring the line between psychological breakdown and supernatural retribution.

Plot (Full Detailed Retelling)

The story begins with the narrator addressing the reader directly, confessing that he is about to die the next day and feels compelled to write down his tale. From the start, he warns that his story will seem incredible, but insists it is true. His tone mirrors that of The Tell-Tale Heart: defensive, erratic, and disturbingly calm.

As a child, the narrator describes himself as gentle and kind. He loved animals deeply and was happiest in their company. When he married young, his wife shared this passion, and together they filled their home with birds, rabbits, a dog, a monkey, and most importantly, a large black cat named Pluto. The narrator describes Pluto as a remarkably intelligent and affectionate animal, his closest companion, and almost a soulmate.

But as the years pass, the narrator falls into the grip of alcoholism. Drink begins to warp his personality. He grows moody, irritable, and violent, lashing out at both his wife and his pets. The once gentle man becomes cruel. Yet through all this, Pluto remains loyal.

One night, returning home drunk, the narrator imagines that Pluto is avoiding him. In a fit of rage, he seizes the cat. When Pluto scratches him in self-defense, the narrator’s anger turns to madness. He takes out a penknife and gouges out one of Pluto’s eyes.

The next morning, hungover and horrified, he feels some remorse but only faintly. The cat heals, though it now shuns him in fear. The man’s guilt turns into irritation, then hatred. Finally, in an act of pure brutality, he ties a rope around Pluto’s neck and hangs him from a tree in his garden. He claims he kills the cat not out of anger, but because he knows it is wrong that the perversity of doing evil for evil’s sake has possessed him.

That very night, tragedy strikes. His house catches fire. The narrator, his wife, and their servant narrowly escape, but the home is reduced to ashes. The next day, the narrator inspects the ruins and discovers something strange: on one wall, still standing, is the image of a gigantic cat with a rope around its neck, imprinted in the plaster. The neighbors are astonished. The narrator tells himself it must have been some natural accident—the neighbors throwing the dead cat into his window during the fire, causing the outline to appear. Yet deep down, he feels the image is a supernatural omen of guilt.

Haunted but trying to forget, he begins to drink even more. Then one night in a tavern, he notices another black cat, remarkably similar to Pluto. This cat is slightly larger, but it too has one missing eye. It follows him home, and his wife, delighted, adopts it. At first, the narrator tolerates the animal, but soon he begins to hate it. The new cat is overly affectionate, constantly underfoot, and it inspires in him a loathing he cannot explain.

Over time, he notices something peculiar: on the cat’s chest, the white patch of fur seems to change shape. Slowly, it takes on the outline of a gallows. To the narrator, this is no coincidence it feels like a symbol of his crime and a prophecy of his doom.

The more he drinks, the more violent he becomes. His wife tries to calm him, but one day, while descending into the cellar with her and the cat, his rage explodes. Enraged at the animal’s presence, he seizes an axe to kill it. His wife intervenes, grabbing his arm. In fury, he turns the weapon on her instead, striking her dead.

Now faced with a corpse, he must hide the evidence. He considers cutting it up, burying it in the yard, or throwing it into the well. But instead, he finds a more clever solution. In the cellar is a hollow section of wall. He pries it open, places his wife’s body inside, and carefully seals it back with mortar. The concealment is perfect. No trace remains.

As for the cat, it has disappeared. Relieved, the narrator feels triumphant his crime is complete. Days pass, and the police arrive to investigate. The narrator is calm, even smug. He leads them through the house and eventually down to the cellar. Convinced of his own cleverness, he boasts of the house’s solid structure. To prove his point, he raps upon the very wall where his wife’s body lies hidden.

At that instant, a sound erupts from behind the bricks a long, loud, wailing cry. It is neither human nor animal, but a mixture of both: a shriek of horror that chills everyone present. Shocked, the police tear down the wall, and there, standing upon the corpse of the wife, is the missing black cat alive and howling.

The narrator realizes too late that he has sealed the animal inside the tomb with his wife’s body. His crime is exposed, and his downfall complete.

Themes & Analysis

- Alcoholism & Madness The narrator’s descent into cruelty is tied to his alcoholism. Poe, who himself struggled with drink, uses it to show how addiction destroys morality and reason.

- Cruelty & Perversity The idea of doing evil simply because one can, a self-destructive impulse, is central to the story. The narrator admits he harms the cat because he knows it is wrong.

- Supernatural vs. Psychological Was the cat a supernatural avenger, or simply an ordinary animal onto which the narrator projected his guilt? Poe leaves this ambiguous, heightening the horror.

- Guilt & Retribution Just like in The Tell-Tale Heart, guilt refuses to stay buried. The cry of the cat becomes the symbol of justice that unmasks the crime.

Why It’s Famous

- A classic Gothic horror story blending domestic realism with the uncanny.

- Frequently studied for its themes of guilt, perversity, and the unreliable narrator.

- Considered one of Poe’s most shocking works due to its violence and psychological depth.

- Adapted into films, radio, and even referenced in modern horror culture.

Moral / Message

One cannot escape guilt or justice. Acts of cruelty, especially against the innocent, will eventually destroy the perpetrator.

3.The Fall of the House of Usher (1839)

📖 Background

First published in 1839 in Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, The Fall of the House of Usher is one of Edgar Allan Poe’s most celebrated works. It embodies Gothic horror at its finest, with themes of madness, decay, isolation, and the supernatural. The story is told through the eyes of an unnamed narrator, allowing the reader to slowly uncover the mystery of the Usher family and their crumbling ancestral home.

Full Detailed Summary

The tale begins with the narrator traveling alone through a dreary countryside, approaching the estate of his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher. From the very first glimpse, the mansion inspires dread. The building is vast, gloomy, and ancient, surrounded by a tarn (a dark, stagnant lake) that mirrors its bleak image. The narrator notes the house’s fissures, its decaying walls, and its oppressive atmosphere that fills him with unease.

He has come at the request of Roderick Usher, who wrote a letter describing his illness and begging for companionship. Upon entering, the narrator is struck by the morbid silence and the sense of melancholy that hangs in the halls. Inside, he finds Roderick thin, pale, with large, luminous eyes, and a nervous, fragile demeanor. His friend appears a mere shadow of the boy he once knew.

Roderick explains his affliction: he suffers from acute sensitivity to light, sound, texture, and even taste. His nerves are constantly on edge. He also confesses that his twin sister, Madeline Usher, is gravely ill with a mysterious disease that doctors cannot cure. She drifts through the house like a ghost, often falling into cataleptic trances states where she seems dead but is not.

The narrator tries to cheer Roderick with conversation, reading, and music, but he feels increasingly disturbed by the oppressive atmosphere. Roderick often plays haunting tunes on his guitar and composes strange poems, including “The Haunted Palace,” which describes a noble palace overtaken by evil forces a clear reflection of the Usher family’s decline.

Soon after, Madeline succumbs to her illness or so it seems. Roderick insists on entombing her body temporarily in a vault within the house rather than burying her in the family graveyard. The narrator helps him place her in a coffin and seal her away in the underground chamber. During this grim task, the narrator notices a disturbing detail: Madeline’s cheeks still carry a faint blush, and her lips are not entirely pale. Yet he dismisses it, attributing it to her illness.

Days pass. Roderick grows increasingly agitated, wandering the halls like a man haunted. The narrator, too, feels the oppressive weight of the house pressing on his spirit. One stormy night, a violent tempest shakes the mansion. To calm Roderick, the narrator begins reading aloud from a medieval romance, The Mad Trist of Sir Launcelot Canning.

As he reads of a knight breaking into a hermit’s dwelling, strange echoes resound through the house the very sounds described in the book seem to come alive: cracking wood, clanging metal, shrieks. Terrified, the narrator looks to Roderick, who sits rigid, eyes wide with terror.

Finally, Roderick confesses what he has feared all along: they buried Madeline alive. Her illness was a trance, not death, and he can feel her presence moving within the house. At that moment, the heavy doors burst open, and Madeline herself appears. She is bloodied, her white garments stained, her face ghastly with the struggle of clawing her way out of the tomb.

In a final, horrifying moment, she collapses upon her brother. Roderick, overcome with terror and guilt, dies instantly with her in his arms.

The narrator flees the house in terror. As he escapes, he looks back at the mansion. A fissure that had long run down the façade suddenly widens. With a thunderous crash, the entire House of Usher collapses into the tarn, swallowed by the dark waters, leaving no trace behind.

Themes & Analysis

- Decay and Ruin The crumbling house mirrors the decline of the Usher family line, both physically and spiritually.

- Madness and Isolation Roderick’s illness and Madeline’s trance-like states reflect psychological torment and hereditary curse.

- The Supernatural vs. the Psychological Was Madeline’s return a supernatural vengeance, or simply premature burial? Poe leaves it ambiguous.

- Family Curse The Ushers are a decayed aristocratic bloodline, doomed by inbreeding, isolation, and fate.

- Gothic Atmosphere The story is saturated with gloom, storm, mystery, and dread, establishing Poe as a master of Gothic fiction.

Why It’s Famous

The Fall of the House of Usher is often considered the definitive Poe story, a masterpiece of Gothic horror. Its vivid imagery of decay, psychological terror, and the merging of human fate with architecture has inspired countless adaptations in literature, film, and art. The collapsing mansion remains one of the most powerful symbols of ruin in all of Gothic literature.

4. The Masque of the Red Death (1842)

📖 Background

First published in 1842, The Masque of the Red Death is one of Poe’s most allegorical and haunting works. Unlike his other tales that focus on individual characters’ descent into madness, this story takes on a broader, almost fable-like quality. It explores human arrogance in the face of mortality and delivers a chilling reminder: no wealth, no wall, and no disguise can protect anyone from death.

Full Detailed Summary

The story begins in a land ravaged by a terrible plague known as the Red Death. This disease is swift and horrifying it begins with sharp pains and dizziness, progresses to uncontrollable bleeding from the pores, and ends in death within half an hour. Whole villages are emptied, and despair hangs over the country like a shroud.

But amidst the suffering, Prince Prospero, a wealthy and eccentric nobleman, refuses to submit to fear. He believes his riches and ingenuity can outwit death itself. To protect himself and his court, he gathers a thousand of his closest friends knights, ladies, entertainers, musicians, and courtiers and retreats into the safety of one of his fortified abbeys.

This abbey is no ordinary castle. It is vast, magnificent, and heavily guarded. Its gates are welded shut, its walls thick and impenetrable. Outside, the plague ravages the land, but inside, Prince Prospero and his companions indulge in luxury, music, and feasts. The world beyond their walls is forgotten; sorrow and compassion have no place within.

To banish all thought of death, Prospero arranges a grand masquerade ball. The ball is unlike any other lavish, bizarre, even grotesque. The prince delights in the unusual and encourages costumes that are strange, monstrous, and fantastical. The guests dance through halls filled with music, laughter, and wine. It is a celebration of life, a mockery of death.

But the true centerpiece of the story is the suite of seven rooms where the masquerade takes place. Each room is decorated in a single color:

- Blue Room draped in blue, with blue stained-glass windows.

- Purple Room rich with purple hangings and light.

- Green Room vibrant and lush in tone.

- Orange Room glowing with fiery shades.

- White Room pale, chilling, and ghostly.

- Violet Room somber and shadowy.

- Black Room with Red Windows the most terrifying of all. Draped in black velvet, with scarlet-tinted windows, it creates a blood-red glow. This room is avoided by most of the guests, for it inspires dread.

Inside the seventh room also stands a great ebony clock. Tall and ominous, it chimes each hour with a deep, heavy sound that echoes through the chambers. Whenever it strikes, the music halts, the dancers freeze, and an uneasy silence grips the guests. But once the chimes fade, laughter resumes nervous, but desperate to drown out the reminder of passing time.

At the height of the revelry, as midnight approaches, the chimes of the ebony clock thunder twelve times. This time, the silence is deeper, more oppressive. When the last chime fades, a stranger appears among the masqueraders.

The figure is tall, cloaked in grave-like garments, and wears a mask so realistic it chills the blood. Unlike the other grotesque costumes, this one is no jest it resembles a corpse struck by the Red Death itself. Its face is spotted with crimson, its garments stained with the signs of plague.

The crowd shudders. Even the boldest guests recoil in horror. Anger rises in Prince Prospero, who views the stranger’s appearance as a mockery of his authority. He demands that the figure be seized and unmasked. Yet as the masked intruder moves silently through the rooms, none dare to touch it. The revelers shrink away, parting before him as he passes from chamber to chamber.

Finally, with rage boiling, Prospero seizes a dagger and pursues the figure himself. He chases it through the suite of rooms until it reaches the final chamber the black-and-red room. But as Prospero lifts his weapon, the figure turns, and with a single glance, the prince collapses lifeless to the floor.

The horrified guests rush forward to seize the figure, but when they tear away the mask and cloak, they find nothing beneath no form, no body. The intruder is not a man but the embodiment of the Red Death itself.

One by one, the revelers fall where they stand, blood seeping from their pores, until all lie dead upon the floor. The Red Death, denied no longer, claims its victory.

And in the end, the last line of the story tells us that “Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

Themes & Analysis

- Inevitability of Death The story’s central theme: no one, not even the wealthy and powerful, can escape mortality.

- Arrogance and Denial Prospero’s attempt to hide from death reflects human arrogance in thinking we can outwit fate.

- Time as an Enemy The ebony clock reminds everyone of time slipping away, foreshadowing the unavoidable arrival of death.

- The Seven Rooms Often seen as an allegory for the seven stages of life, ending with death (the black-and-red room).

- The Masquerade Symbolizes how humans mask their fears, distracting themselves with pleasure until reality forces its way in.

Why It’s Famous

The Masque of the Red Death is famous for its allegorical depth and visual symbolism. Its imagery the masquerade, the seven rooms, the ebony clock has inspired countless adaptations in art, theater, and film. It remains one of Poe’s most powerful statements about mortality and the futility of denying death.

5. The Pit and the Pendulum (1842)

Background

Published in 1842, The Pit and the Pendulum is one of Edgar Allan Poe’s most suspenseful and terrifying tales. Unlike his supernatural stories, this one is grounded in psychological horror and human endurance. It places the reader inside the mind of a man subjected to cruel tortures during the Spanish Inquisition, and explores themes of fear, time, and the relentless struggle for survival.

Full Detailed Summary

The story begins with the unnamed narrator being condemned to death by the Inquisition. He remembers the shadowy tribunal of black-robed judges, their stern voices, and the chilling pronouncement of his sentence. Darkness overwhelms him as he faints, and when he awakens, he finds himself in utter blackness.

At first, he believes he has been buried alive. The air is heavy, the silence suffocating. But as he stretches his hands, he feels the cold stone floor beneath him and realizes he is in a vast, pitch-black chamber. Carefully, he begins to explore, crawling and counting his steps to estimate the room’s size.

As he gropes along the wall, his robe snags on something, and he stumbles forward. His hand brushes empty air. Terrified, he drops a fragment of his clothing into the void and hears no sound of it striking bottom. He realizes with horror that he has nearly fallen into a circular pit in the center of the chamber. This pit, he understands, must be a trap death for the unwary prisoner who dares to wander in the dark.

Exhausted by fear and hunger, the narrator eventually falls asleep. When he awakens, he finds bread and water placed mysteriously beside him. Though he dreads poison, hunger compels him to eat. He knows his captors intend not to kill him quickly but to toy with him, to make him suffer.

After another period of unconsciousness, he awakens to find himself bound. He is strapped to a wooden framework, lying on his back. His arms and legs are tied with bandages, leaving him unable to move. Above him, a strange motion catches his eye.

From the ceiling descends a massive pendulum, a crescent-shaped blade with a sharp, glistening edge. It swings slowly, rhythmically, from side to side, like a great scythe. At first it hangs high above him, but with each swing, he realizes it descends lower inch by inch, closer to his chest.

The narrator is paralyzed with terror. He watches helplessly as time stretches into eternity, measured by the pendulum’s dreadful rhythm. He can hear the hiss of its blade slicing the air. Its descent is agonizingly slow, designed not to kill swiftly but to torture him with anticipation.

As the pendulum inches closer, despair threatens to overwhelm him. But desperation breeds ingenuity. He notices that the ropes binding him are coated with a greasy substance meat. And around him, rats swarm from the pit’s darkness, drawn by the scent.

In a moment of terrible clarity, he smears the remaining food onto his bindings. The rats, ravenous and frantic, gnaw at the ropes. The process is excruciatingly slow, but finally just as the pendulum’s blade grazes his chest the ropes snap, and he rolls free. The pendulum, having lost its victim, swings harmlessly to one side.

But the torment is not over. The pendulum retracts into the ceiling, and the narrator realizes his escape has been anticipated. The walls of the chamber begin to glow with fiery heat, and they start to move inward, slowly pushing him toward the central pit.

The room grows smaller and smaller, the heat searing his flesh, the walls driving him closer to the abyss. He faces a final, unspeakable choice: leap into the pit, the unknown black void, or be crushed by the burning walls.

In a moment of despair, he stands at the very brink, ready to plunge into the abyss. But just as he prepares for death, the walls halt. A voice shouts above him, and a hand seizes his own. It is the hand of General Lasalle, leading the French army, which has stormed Toledo and ended the Inquisition.

The narrator collapses into the arms of his rescuer, trembling and broken, but alive.

Themes & Analysis

- The Psychology of Fear Poe delves deep into the torment of anticipation. The pendulum’s slow descent represents the agony of waiting for death.

- Time as a Weapon The pendulum’s steady swing is both a literal weapon and a metaphor for time’s unstoppable march toward death.

- Human Resilience Despite the horrors, the narrator clings to reason and ingenuity, using rats to escape his bonds.

- Hope vs. Despair Just as the narrator is about to surrender to despair, salvation arrives, showing the thin line between hopelessness and deliverance.

- The Pit as Ultimate Death The pit symbolizes the void, annihilation, and the unknown terror of what lies beyond life.

Why It’s Famous

The Pit and the Pendulum is one of Poe’s most cinematic stories, filled with vivid imagery and unbearable suspense. Its themes of torture, time, and human endurance have made it a classic of horror literature. It has been adapted into films, stage plays, and even referenced in modern media, proving the timelessness of Poe’s vision.

6. The Masque of the Red Death (1842)

📖 Background

Published in 1842, The Masque of the Red Death is one of Poe’s most allegorical works. Unlike his detective or psychological tales, this story is a dark parable about mortality, portraying the futility of trying to escape death. It is brief in its original form, but loaded with Gothic imagery, symbolism, and a haunting inevitability.

Full Detailed Summary

The tale opens with the description of a dreadful plague that has ravaged the land: the Red Death. It is no ordinary sickness it strikes quickly and brutally. Its victims suffer sharp pains, sudden dizziness, and most horrifyingly, bleeding from the pores of the skin. Within half an hour of infection, the body is lifeless, leaving behind blood-stained corpses that terrify all who see them. The disease spreads with relentless swiftness, leaving entire villages depopulated.

In the midst of this horror, Prince Prospero, a wealthy and eccentric ruler, refuses to be a victim. He is described as bold, happy, and perhaps a little mad. Unlike his terrified subjects, he is not interested in despair or mourning. Instead, he devises a plan: to lock himself away in a fortified abbey, bringing with him a thousand friends from among the nobility knights, ladies, musicians, dancers, and entertainers.

Prospero’s abbey is lavishly stocked with food, wine, and amusements. The outside world may be dying, but inside, there will be laughter, music, and revelry. The prince is determined to ignore the plague by indulging in endless celebration, believing his wealth and walls can shield him from the inevitable.

After months of seclusion, Prospero throws a grand masquerade ball a festival of decadence, where the guests dress in grotesque costumes, dancing in a swirl of color and extravagance. The ball takes place in a suite of seven rooms, each decorated in a different hue, connected in such a way that one can only see one chamber at a time, creating a winding passage of shifting atmospheres.

The rooms are arranged as follows:

- Blue Room with windows of blue stained glass.

- Purple Room draped in purple, with stained glass matching.

- Green Room decorated in green.

- Orange Room glowing with orange hues.

- White Room bright with white drapery.

- Violet Room shrouded in deep violet.

- Black Room the most striking, draped in black velvet, with scarlet-red stained glass windows.

The final, black chamber is the most dreadful. Few guests dare to linger there, for it holds a giant ebony clock that strikes each passing hour with a sound so deep, so resonant, that the music of the orchestra halts, the dancers freeze, and the laughter dies into silence. Each time it tolls, the revelers grow pale, and once the echoes fade, nervous laughter resumes and the party continues. The clock serves as an ominous reminder of time, of mortality, of the inevitability of death.

At the height of the revelry just as the midnight hour is struck the guests become aware of a new figure among them. Unlike the playful masqueraders, this one is terrifying. He is dressed not in flamboyant or comical costume, but in the robes of a grave shroud. His mask resembles the rigid features of a corpse. Most horrifying of all, his attire is spattered with blood, making him look like a victim of the Red Death itself.

A murmur of horror spreads through the guests. The revelers recoil in terror, then outrage. How dare someone bring such a ghastly mockery into their sanctuary of pleasure? Even Prospero, usually unflappable, is filled with fury. With trembling voice and burning eyes, he orders the intruder to be seized and unmasked, that his identity may be revealed. But as the figure moves silently through the rooms, the crowd shrinks back, unwilling to touch him.

Finally, Prospero, maddened by rage and shame, rushes after the figure with a dagger in hand. He chases it through the winding chambers blue, purple, green, orange, white, violet until he reaches the final, black room.

The intruder stops, turns slowly to face the prince. Prospero lets out a cry and falls dead to the floor.

The guests, summoning their courage, seize the figure at last. But when they tear away its garments and mask, they find nothing beneath no form, no flesh, only emptiness.

In that moment, realization dawns: the Red Death itself has entered the abbey. One by one, the revelers collapse, their bodies stained with the crimson horror. The plague claims all within, sparing no one.

The story closes with chilling finality:

“And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

Themes & Analysis

- The Inevitability of Death The story is a parable reminding that no wealth, walls, or diversions can protect humanity from mortality.

- Time as a Harbinger The ebony clock is a constant reminder that death is approaching with each passing hour, no matter how much one ignores it.

- Decay Beneath Extravagance The lavish party masks the despair outside, but ultimately, the revelers cannot hide from reality.

- Symbolism of the Seven Rooms The progression of colored rooms may represent the stages of life, culminating in the black room (death).

- Hubris of Humanity Prince Prospero represents arrogance the belief that power and privilege can conquer nature’s laws.

Why It’s Famous

The Masque of the Red Death is one of Poe’s most allegorical Gothic masterpieces, blending plague imagery with timeless symbolism. Its haunting imagery, from the colored rooms to the figure of the Red Death, has cemented its place in Gothic literature, inspiring countless adaptations in film, theater, and art.

7. The Cask of Amontillado (1846)

📖 Background

Published in 1846, The Cask of Amontillado is one of Edgar Allan Poe’s darkest and most chilling tales of revenge. Unlike his supernatural stories, this one is grounded in human cruelty and cunning. Written in the voice of a proud killer, the story is both a confession and a terrifying exploration of pride, deceit, and vengeance.

Full Detailed Summary

The story begins with the narrator, Montresor, declaring that he has suffered “a thousand injuries of Fortunato,” but when Fortunato ventured upon an insult, Montresor swore revenge. He does not reveal the insult, leaving the reader in mystery, but his tone makes it clear he feels his honor has been wounded, and for him, revenge must be both carefully planned and flawlessly executed.

Montresor tells us his guiding principle: a wrong is not avenged unless the avenger escapes punishment, and unless the victim knows who has wronged him. It is not enough for Montresor to kill Fortunato he must do it in such a way that his victim realizes why and by whom he is being destroyed.

The opportunity arrives during Carnival season a time of drunken festivity, costumes, and chaos in the city. Fortunato, Montresor’s target, is described as a man deeply proud of his knowledge of wine, though perhaps not as discerning as he believes.

Montresor approaches Fortunato in the streets, who is already intoxicated and dressed in the costume of a jester a motley outfit with a cap of bells, a cruel foreshadowing of the mockery to come. Montresor greets him warmly and claims to have acquired a pipe (a large cask) of rare Amontillado sherry. However, Montresor pretends to be unsure of its authenticity, saying he intends to consult another wine expert, Luchesi, if Fortunato is too busy.

The bait works perfectly. Fortunato, driven by pride and rivalry, insists that Luchesi cannot possibly judge wine as well as he. Eager to prove his superior taste, he agrees to accompany Montresor to his palazzo and into the vaults, where the Amontillado is supposedly stored.

Montresor leads Fortunato through the palazzo, down into the damp catacombs beneath. These underground vaults serve as both wine cellars and burial chambers for the Montresor family. The air grows cold, heavy with nitre (saltpeter) clinging to the walls. Fortunato coughs violently, but Montresor feigns concern, urging him to turn back. Fortunato, prideful and drunk, insists it is nothing, and continues forward in pursuit of the Amontillado.

As they move deeper, Montresor keeps offering him wine first Medoc, then De Grave to keep him drunk and less aware. The jester’s bells jingle with every step, echoing eerily in the darkness. The imagery grows more grotesque, as bones of Montresor’s ancestors are piled along the walls, and shadows stretch long in the torchlight.

Their conversation drifts into unsettling themes. Montresor mentions his family’s coat of arms: a golden foot crushing a serpent, whose fangs are embedded in the heel. The motto: “Nemo me impune lacessit” (“No one provokes me with impunity”). Fortunato laughs drunkenly, not realizing he is the serpent about to strike and be crushed.

At last, they reach a small recess in the deepest part of the catacombs. Montresor tells Fortunato that the Amontillado is inside. Fortunato, stumbling forward, peers in. In that instant, Montresor acts. He chains Fortunato to the granite wall hands shackled above, his body trapped.

Fortunato, stunned, begins to laugh. He thinks it must be a joke, a carnival trick. But Montresor, cold and methodical, produces mortar and stone hidden nearby. He begins to wall up the niche, brick by brick.

At first, Fortunato plays along, laughing nervously, expecting the prank to end. But as the wall rises higher, he sobers. His laughter turns to pleas, then to screams, which echo through the catacombs. Montresor mocks him, noting how well the thick stone walls keep the sound from escaping.

The jingling of the bells grows faint as Fortunato’s voice weakens. In desperation, Fortunato makes one last attempt at humor: “For the love of God, Montresor!” he cries. Montresor, pausing in his work, echoes his words coldly: “Yes… for the love of God.”

But when he calls Fortunato’s name again, there is no reply. Only the faint jingle of the cap’s bells. The silence confirms his death. Montresor finishes the wall, sealing Fortunato inside forever.

The tale ends with Montresor revealing that this happened fifty years ago. No one has disturbed the wall, and Fortunato’s body remains entombed in the darkness. Montresor concludes with chilling satisfaction:

“In pace requiescat!” (Rest in peace).

Themes & Analysis

- Revenge & Pride Montresor embodies the cold, calculated desire for vengeance, while Fortunato’s pride in his wine expertise becomes his fatal flaw.

- Deception & Manipulation Montresor’s false friendship and flattery lure Fortunato to his doom.

- The Gothic Setting Catacombs, bones, and darkness create an atmosphere of horror that mirrors Montresor’s twisted soul.

- Irony Fortunato (whose name means “fortunate”) is anything but lucky. His jester costume symbolizes how Montresor sees him a fool.

- Unreliable Narrator Montresor tells the story as a confession, but never reveals the insult. Readers are left questioning whether the crime was justified or the act of a madman.

Why It’s Famous

The Cask of Amontillado is one of Poe’s most masterful revenge tales, remembered for its chilling first-person narration, claustrophobic atmosphere, and haunting finality. It has inspired countless adaptations and remains a classic study in psychological manipulation and Gothic horror.

7. The Masque of the Red Death (1842)

Full Detailed Summary:

Set in a land ravaged by a deadly plague known as the Red Death, the story begins with the wealthy Prince Prospero, who believes he can outwit death through wealth, power, and seclusion. While his people perish outside, Prospero invites a thousand nobles, courtiers, and entertainers to retreat into his fortified abbey. The abbey is sealed with iron gates, provisions stockpiled, and guards instructed to keep everyone inside until the plague has run its course.

Inside, Prospero creates an atmosphere of extravagant denial. He orders a magnificent masquerade ball, to be held in a suite of seven uniquely decorated rooms. Each chamber is painted in a single, vivid color: blue, purple, green, orange, white, violet, and finally, the seventh room black, with blood-red stained windows. This final chamber creates such an eerie, oppressive atmosphere that most guests avoid it entirely. Within it stands a massive ebony clock that chimes each passing hour. At every toll, the music stops and the revelers fall silent, uneasily reminded of the time slipping away.

As the masquerade continues, guests indulge in wild dances, laughter, and surreal costumes meant to defy fear. But just after midnight, a new figure appears. This figure is unlike the others: it wears garments resembling a funeral shroud and a mask that mimics the visage of a corpse with features marked by the horrific signs of the Red Death. The intruder’s presence shocks and terrifies the crowd.

Enraged that someone would dare to mock their suffering, Prince Prospero demands the figure be seized. But the guests shrink back, too horrified to act. Finally, Prospero himself confronts the figure with a dagger in hand. He pursues it into the black-and-red room, where he collapses dead in an instant.

The courtiers rush forward to unmask the figure, only to discover there is no human beneath the disguise. The apparition is the Red Death itself. One by one, all the revelers succumb to the disease, and in the end, “Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

Themes:

- Inevitability of Death → Wealth, power, and isolation cannot shield anyone from mortality.

- Denial and Decadence → Prospero’s indulgent masquerade is a futile attempt to escape reality.

- Time as a Reminder → The ebony clock symbolizes life’s fleeting nature and the unstoppable march toward death.

Why It’s Famous:

This tale is one of Poe’s most haunting allegories. It captures the inescapable reality of death, while offering lush Gothic imagery. The striking symbolism of the seven rooms and the chilling arrival of the Red Death have made it one of the most anthologized stories in Gothic literature.

8. The Pit and the Pendulum (1842)

Full Detailed Summary:

This story begins in the heart of the Spanish Inquisition, with an unnamed narrator sentenced to death. The charges are never made clear, but the atmosphere is one of dread and hopelessness. He faints as the sentence is declared, and when he awakens, he finds himself in a dark, silent chamber, the walls of which are damp, slimy, and seemingly endless.

As he gropes around the room, he realizes the judges have placed him in a dungeon designed not merely to kill, but to torture the mind through fear. His first great discovery is a circular pit in the center of the chamber wide and deep, with no bottom in sight. He nearly falls into it, realizing this is one possible death awaiting him. The pit symbolizes the unknown terror of death itself.

Later, he is strapped to a wooden board, immobilized, and food is left nearby. Above him swings a giant pendulum blade, razor-sharp, slowly descending with each pass. The pendulum is both a physical danger and a cruel reminder of time ticking away toward death. Each swing comes closer, the hiss of its blade echoing in his ears, amplifying his dread.

In desperation, he devises a clever escape. He smears the food onto the ropes binding him, attracting the hungry rats that scurry around the cell. The rodents gnaw through his restraints just in time, allowing him to roll away as the blade slices through the air where he had lain.

But his relief is short-lived. The walls of the dungeon begin to glow red-hot and slowly move inward, forcing him closer and closer to the pit. The heat, the shrinking space, and the abyss before him seem to guarantee that he will perish in agony.

At the very brink when he is about to fall into the pit he hears trumpets and the clash of voices. The walls stop. A hand pulls him back. The French army has captured Toledo, ending the Inquisition’s reign of terror and saving him at the last possible second.

Themes:

- Fear as Torture → Poe shows how psychological terror is often worse than physical pain.

- Time and Death → The pendulum represents the inevitable passage of time leading to death.

- Hope in Desperation → Even at the edge of death, the human will to survive finds inventive solutions.

Why It’s Famous:

Unlike Poe’s supernatural tales, this story is rooted in real historical terror the cruelty of the Inquisition. The blend of psychological horror, suspense, and the final twist of rescue make it one of his most gripping works. It’s a masterclass in building tension, forcing the reader to feel every second of dread with the narrator.

9. The Black Cat (1843)

Full Detailed Summary:

The narrator of this chilling tale begins by telling the reader that he is about to die executed for a crime so terrible that he feels compelled to confess. From the very start, the story is framed as both a confession and a warning.

He explains that as a child he was gentle and kind, especially toward animals. When he married, he and his wife filled their home with pets, and among them was his favorite a large black cat named Pluto, intelligent, affectionate, and loyal. For years, their bond was unshakable.

But as time passed, the narrator fell into the grip of alcoholism. Drink warped his character: where once he was loving, now he became short-tempered, violent, and cruel. His relationship with Pluto deteriorated. One night, in a drunken rage, he seized the cat, and when Pluto bit him out of fear, the narrator committed an act of unspeakable cruelty he gouged out one of the cat’s eyes.

Pluto slowly recovered, but the bond was destroyed. The once-loving animal now fled from him in terror. Guilt gnawed at the narrator, but instead of reforming, his alcoholism and rage deepened. Finally, in a fit of madness, he took Pluto outside and hanged him from a tree, killing the very creature he once adored.

That night, his house mysteriously burned down, leaving only one standing wall. On it was a strange image: the outline of a giant cat, noose around its neck. The narrator tried to rationalize it as coincidence perhaps a corpse thrown against the wall during the fire but in his heart, unease began to grow.

Some months later, he encountered another black cat, eerily similar to Pluto, except this one had a patch of white fur on its chest. The cat followed him home and soon became a fixture in the household. At first, the narrator welcomed it, even doting on it as a way to ease his guilt. But soon, the similarities to Pluto and the strange white patch that seemed to change shape into something ominous filled him with hatred.

The cat’s affection felt suffocating. It followed him constantly, tripping him on the stairs, staring at him while he slept. The narrator’s unease transformed into loathing, and his mind slipped further into darkness.

One day, while descending into the cellar with his wife and the cat, he seized an axe, intending to kill the animal. His wife, horrified, tried to stop him. In his fury, he turned the weapon on her instead and killed her instantly. To hide the crime, he walled her body up inside the cellar.

For days, he lived smugly, certain that he had committed the perfect crime. The cat had vanished, and he assumed it had run away. When the police came to investigate, he led them confidently through the house. At last, in a moment of arrogance, he rapped upon the very wall where his wife’s body was entombed, declaring the sturdiness of his home.

At that moment, a sound came from behind the wall a long, wailing, chilling cry. The police tore down the bricks and discovered the wife’s corpse. Perched on her head, howling, was the very black cat he thought had disappeared. In sealing the wall, he had unwittingly sealed the creature in with his victim.

The narrator ends his tale with despair: his crime exposed, his life ruined, his fate sealed by the very animal he tried to destroy.

Themes:

- Alcohol and Madness → Poe illustrates how addiction can corrupt love into cruelty.

- Guilt and Retribution → The narrator’s attempt to bury his crime only brings it to light.

- The Supernatural or the Psychological? → Is the cat a real creature, or a manifestation of guilt and fate?

Why It’s Famous:

The Black Cat is one of Poe’s darkest and most disturbing stories. It combines domestic violence, psychological horror, and eerie supernatural suggestion, making readers question whether the cat is truly supernatural or a symbol of the narrator’s conscience. Its brutal honesty about addiction and guilt makes it both horrifying and unforgettable.

10. The Gold-Bug (1843)

Full Detailed Summary:

Unlike most of Poe’s stories drenched in Gothic horror, The Gold-Bug is a tale of mystery, adventure, and cryptography. It begins on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, where the narrator visits his eccentric friend William Legrand. Legrand, once wealthy, now lives in poverty in a small hut with his loyal servant, Jupiter.

Legrand is a peculiar man prone to sudden bursts of passion and obsession. During one of his excursions, he discovers a strange gold-colored beetle with a skull-like pattern on its back. Though it seems trivial, Legrand becomes oddly fixated on it. He sketches the insect for the narrator, but when the narrator examines the drawing, he notices it doesn’t look much like a beetle at all instead, it resembles a skull.

Soon, Legrand grows increasingly secretive, convinced the insect is linked to a great discovery. He studies maps, old manuscripts, and symbols, his mind racing with possibilities. The narrator fears his friend has gone mad.

One night, Legrand insists that the narrator accompany him and Jupiter on a mysterious expedition. Reluctantly, the narrator agrees. Legrand provides detailed instructions: they carry tools, a lantern, and rope into the woods. After a long trek, they arrive at an ancient tree a massive tulip tree that towers above the forest.

Legrand orders Jupiter to climb the tree with the gold-bug tied to a string. Suspicious but loyal, Jupiter obeys. When he reaches a high branch, Legrand instructs him to drop the bug through the eye socket of a skull nailed to the branch. The narrator is baffled, believing his friend has descended into lunacy.

Legrand marks the spot on the ground where the bug falls, and after making careful measurements, he directs them to dig. They labor deep into the night, shoveling furiously, but uncover nothing except bones the remains of an old grave. The narrator is both horrified and frustrated, convinced the endeavor is madness.

Yet Legrand refuses to give up. He recalculates the drop point, realizing Jupiter made a small mistake he dropped the bug through the wrong socket of the skull’s eyes. Correcting the error, they dig again at a new spot. This time, the shovels strike something solid.

With growing excitement, they uncover a large wooden chest, buried deep in the earth. Together, they pry it open and are blinded by the glittering contents inside. The chest is filled with gold coins, jewels, precious stones, and ornaments of immense value. The discovery is overwhelming, a pirate’s hoard beyond imagination.

Later, Legrand explains everything:

- The gold-bug itself was not magical, but it led him to find a parchment with a cryptic message.

- On the parchment was a coded cipher, which he painstakingly deciphered. The message, once decoded, revealed instructions for finding the treasure of the infamous pirate Captain Kidd.

- The skull nailed to the tree was a marker, left centuries before, to guide the recovery of the treasure.

The narrator marvels at his friend’s intelligence, realizing Legrand was never mad but brilliantly resourceful. The discovery of Kidd’s treasure transforms Legrand’s life, restoring his fortune and proving the rewards of perseverance, logic, and daring adventure.

Themes:

- Cryptography and Logic → Poe’s fascination with puzzles shines in the story’s cipher, showcasing his love of codes.

- Treasure and Greed → The lure of wealth, but also the discipline needed to achieve it.

- Reason vs. Madness → What appears to be obsession and insanity turns out to be genius.

Why It’s Famous:

The Gold-Bug became one of Poe’s most popular and widely read works during his lifetime. It mixed Gothic suspense with intellectual thrill, adventure, and puzzle-solving, captivating readers. It also foreshadowed the rise of the detective and adventure genres.

For More Stories

Conclusion

Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories remain timeless masterpieces of Gothic horror, mystery, and psychological suspense. From the eerie heartbeats in The Tell-Tale Heart to the crumbling madness of The Fall of the House of Usher and the cryptic treasure hunt in The Gold-Bug, Poe explored the darkest corners of the human mind while keeping readers on the edge of their seats. His works are not just tales of fear they are profound studies of madness, guilt, obsession, love, and death.

Whether you’re drawn to his haunting Gothic settings, his clever use of mystery and cryptography, or the way he masterfully blends the supernatural with psychological depth, Poe’s stories continue to inspire readers and writers alike. More than 180 years later, his legacy as the master of Gothic literature and short fiction remains unmatched.

If you’re looking for tales that will chill your spine, spark your imagination, and leave you thinking long after you finish reading, Edgar Allan Poe’s stories are the perfect place to begin.

Author

“Written by Namra Asim, storyteller and content creator at InspiredNap. Passionate about weaving magical adventures and meaningful lessons into stories that spark imagination and inspire hearts.”